Carbon management in Germany (II): emissions, potentials, and costs for CCUS

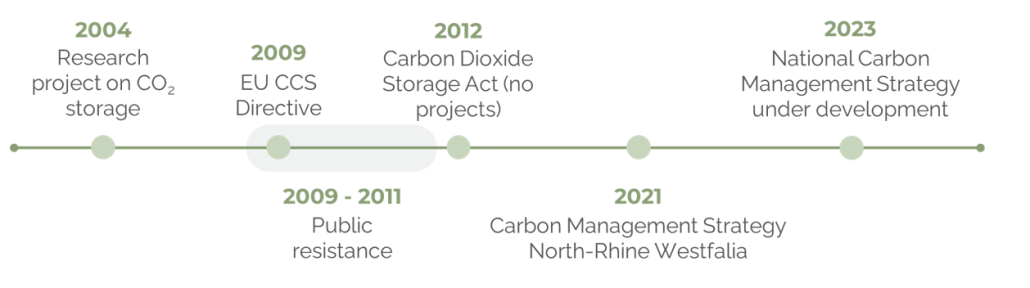

In this second article of the series on carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) in Germany, carboneer analyses the emission profiles of German industries and associated CCS potentials and costs. Review the first article on the developments around carbon management in Germany from a political and climate perspective here. Follow carboneer to access all articles, covering the general historical and political context of the topic, and highlighting developments and implications for the sectors steel, cement, lime, chemicals, and waste incineration.

Focus on industrial emissions

The energy sector, specifically electricity generation in coal and gas power plants, will most likely be excluded from any CCUS activities as the Carbon Management Strategy (CMS) of Germany is geared towards residual (hard-to-abate) and process-related emissions in the industrial sector. Still, the energy sector is the largest contributor to German CO2 emissions: In 2021 the energy sector emitted 238 Mt of CO2, accounting for 35% of total CO2 emissions. Most of the emissions from existing coal and gas power plants are however expected to be replaced by renewable sources or green hydrogen utilization, therefore limiting the scope for CCUS applications. Some potential however remains, mostly through CCUS applications in waste and biomass power plants.

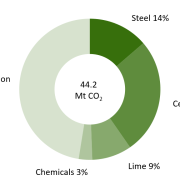

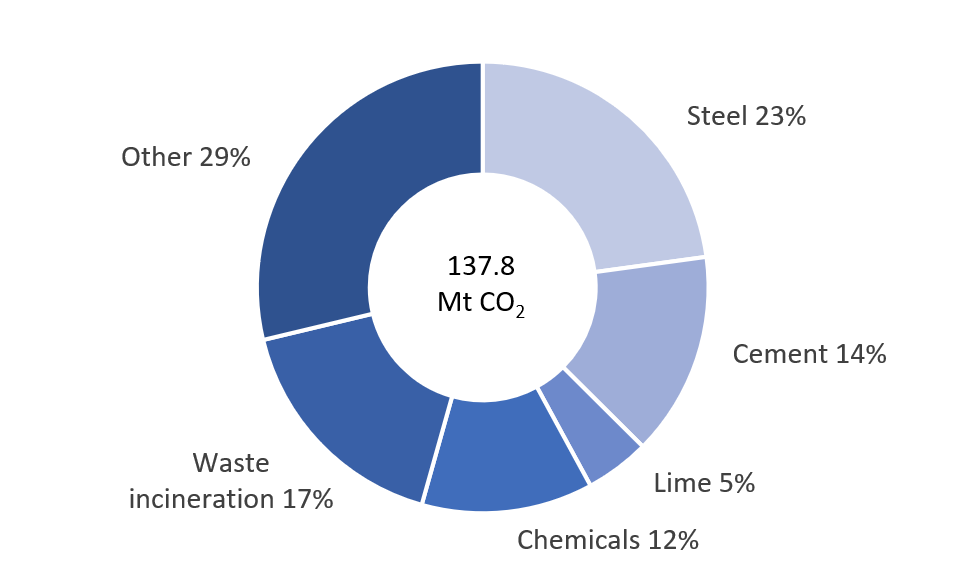

The focus for CCUS activities will thus be on the industrial sector, the second largest contributor to CO2 emissions in Germany. In 2021, industrial facilities were responsible for 168 Mt of CO2 emissions, accounting for 25% of total CO2 emissions. The largest share of industrial emissions originates from large installations that are subject to the EU Emission Trading System as well as from waste incineration facilities. These installations emitted a total of 137.8 Mt CO2 in 2021 (cf. Figure 1), with largest contributions from steel production (31.5 Mt), waste incineration (23.3 Mt), cement production (20.1 Mt), the production of chemicals (16.9 Mt), and lime (6.4 Mt).

The CCS potential in the industrial sector in Germany

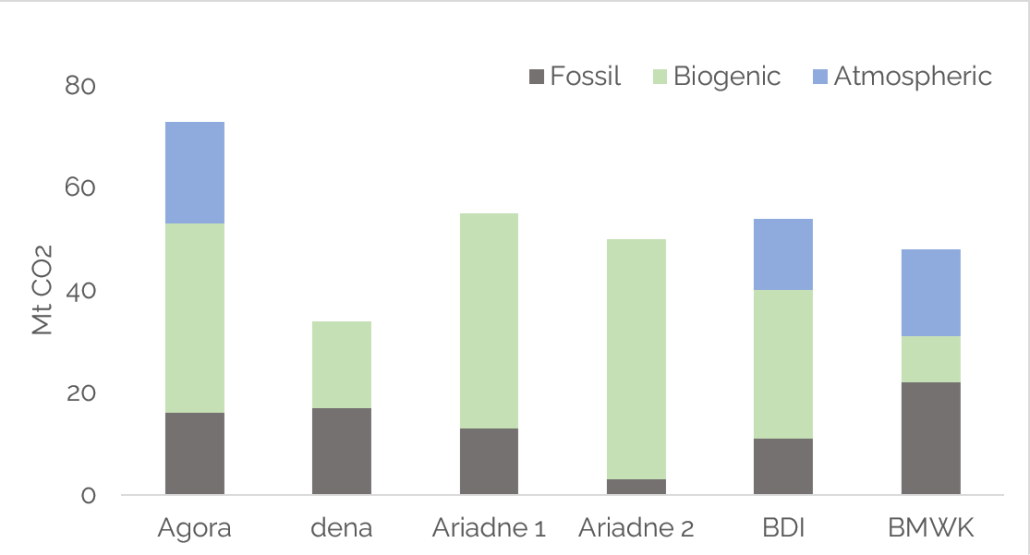

Three quarters of emissions in the industry are related to energy use and are to be abated using renewable energy. Approximately one quarter of the industrial emissions are process-related and originate from the utilization of carbon-containing materials in production. Process-related emissions are difficult to avoid and the five major climate neutrality studies for Germany (see part I) highlight the significant role of CCUS for emission mitigation or CO2-recycling in industry.

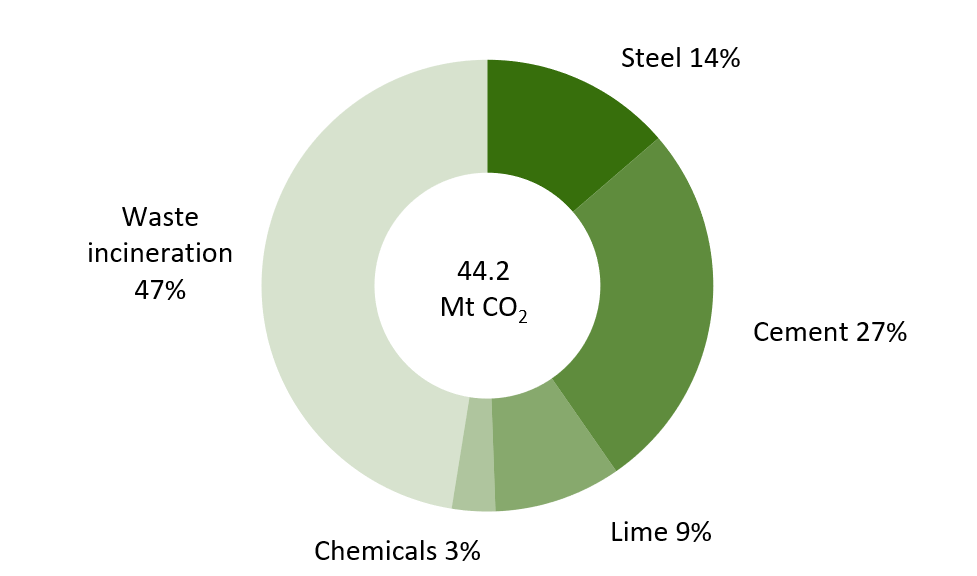

When calculating the CCS potential, it is important to notice that not all process-related emissions can be captured. Depending on industry and the dispersion of emission sources, the share of capturable emissions ranges from 45% in the chemical industry to 90% for waste incineration facilities. Following this methodology, the amount of technically capturable CO2 emissions from large industrial and waste incineration facilities in Germany amounts to 44.2 Mt (cf. Figure 2).

Considering economic feasibility and alternative technological pathways for decarbonization, the ultimately relevant CCUS potential shrinks even further. While lime, cement, and waste incineration will need to capture CO2 due to a lack of technological alternatives, the use of green hydrogen may be the primary decarbonization route for steel production. The chemical industry will continue to depend on carbon-containing materials to produce basic chemicals, but might shift from fossil to biogenic and atmospheric sources, or build on recycled carbon from other industrial sectors. A more detailed analysis of the different sectors and their CCUS readiness will follow in future articles of this series.

Infrastructure and costs

To enable the transport of captured CO2 to potential storage sites or consumers, suitable infrastructure is necessary. The development of CO2 transport infrastructure is critical for the success of carbon management, and the pace of its development can significantly influence the entire progress of CCUS applications. By 2030, first large-scale CO2 transport infrastructures in Germany are necessary, where the mode of transport will depend on the scale and intended use of the CO2. Rail, trucks, ships, and pipelines can all be viable options. A pipeline connection is particularly useful for large industrial sites and CCUS clusters that generate significant amounts of CO2 to be transported over longer distances to storage facilities. However, for decentralized sites such as lime and cement plants, the most efficient handling of captured CO2 has yet to be identified. Local production of synthetic fuels is one of the possible options. A country-wide CO2 pipeline system connecting all major point sources is unlikely to develop, but pipelines for large industrial clusters will be necessary in the medium to long term. Furthermore, some oil and gas companies are already working on developing pipelines for exporting CO2 generated in Germany to storage sites in the North Sea.

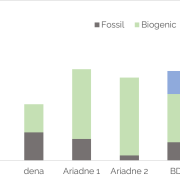

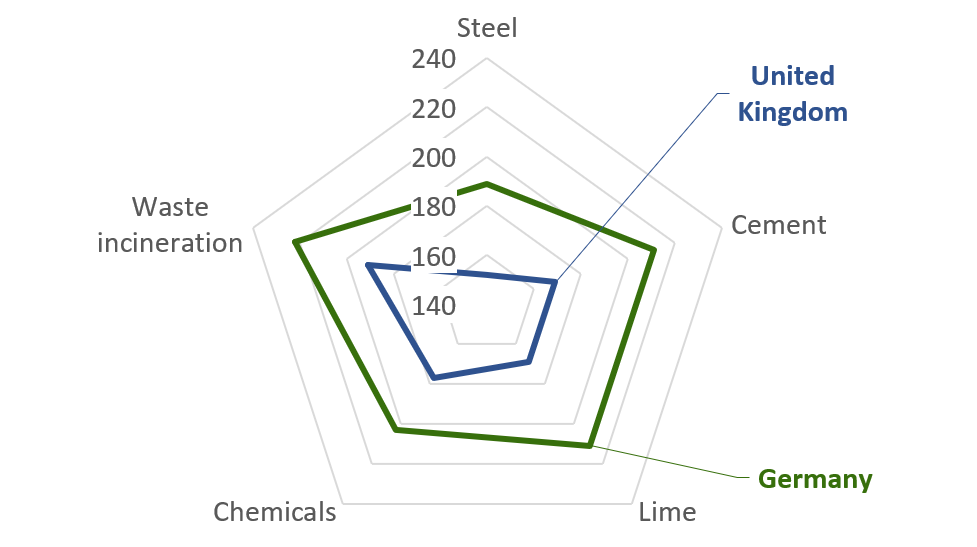

While CCS costs (including capture, transportation, and storage) are relatively homogeneous across sectors, the current unavailability of storage capacity within Germany makes pure CCS implementation relatively expensive (cf. Figure 3) when compared to a country such as the United Kingdom, which has better access to storage sites (e.g. the North Sea). High costs of approximately 200 EUR/t CO2 for CCS applications in Germany already point at the need for incentive and support mechanisms to bring carbon management to an industrial scale.

Policymakers in Germany have to make the decision whether depleted natural gas reservoirs and saline aquifers in northern Germany and under the German North Sea are suitable CO2 storage sites, or if exporting CO2 through international collaborations and storing it in the North Sea and Norwegian Sea is a more politically acceptable option.

In the upcoming articles of this series, we investigate the attractiveness and readiness of the above industrial sectors for CCS applications based on indicators such as the regulatory framework, competing decarbonization options and other sector specific characteristics.

This article is based on a study by carboneer for the Trade Commissioner Service of the Canadian Embassy to Germany.

Sources

CATF (2022) The cost of carbon capture and storage in Europe. Available at: https://www.catf.us/ccs-cost-tool/ (Accessed: 27 March 2023).

DEHSt (2022) Treibhausgasemissionen 2021: Emissionshandelspflichtige stationäre Anlagen und Luftverkehr in Deutschland (VET-Bericht 2021). Available at: https://www.dehst.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/VET-Bericht-2021.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=7 (Accessed: 27 March 2023).

EEA (2022) Industrial Reporting database, May 2022, 7 March. Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/industrial-reporting-under-the-industrial-6 (Accessed: 27 March 2023).