Carbon markets: Which role does biomass play?

Although compliance and voluntary carbon markets vary in scope, mechanisms and participants, biomass occupies a unique place. In compliance carbon markets such as the EU ETS, participants are obliged to monitor and report their emissions and ultimately pay for them. Using biomass in industrial facilities can allow for reduced financial burdens. Regulators set rules around biomass use and sustainability criteria to comply with. A large part of voluntary carbon market credits is generated by nature-based solutions, including forestry and other biomass-related projects. These projects are however under intense scrutiny due to issues regarding transparency and associated climate claims. Novel carbon removal solutions with biomass as feedstock show promising development and renewed regulatory oversight could restore trust.

Which CO2 and which carbon markets?

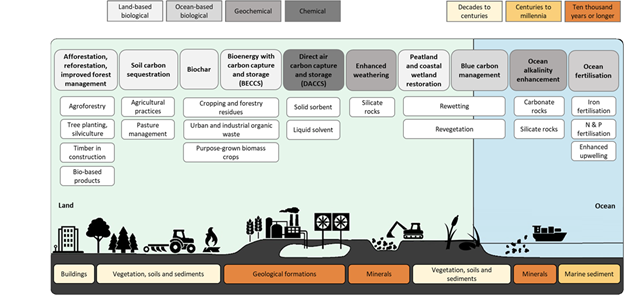

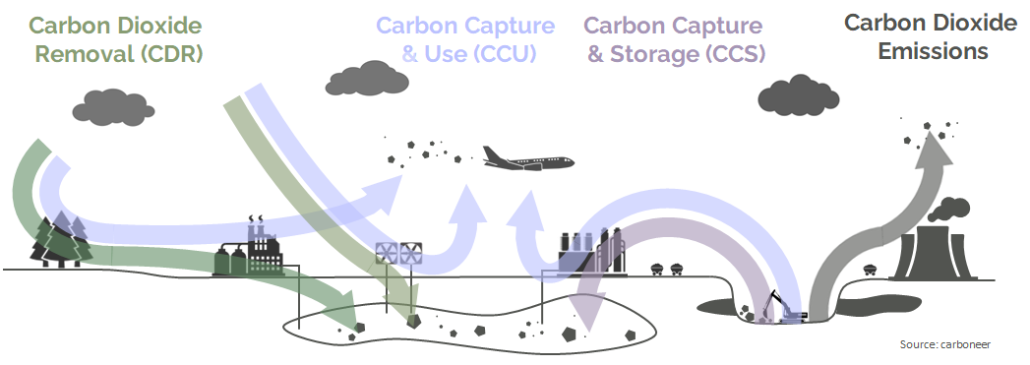

To assess the relevance of carbon markets for biomass and vice versa, requires an understanding of different types of emissions and how carbon markets account for them. The sources of CO2 emissions and their final sink can be categorized into four main pathways (Figure 1).

- Unabated carbon emissions from fossil sources add emissions to the atmosphere (grey and black)

- Abated emissions from fossil sources through carbon capture and storage (CCS) with long-term storage might not add additional GHG emissions to the atmosphere (purple)

- Negative emissions through nature-based or technological carbon dioxide removal (CDR) solutions taking CO2 out of the atmosphere and storing it durably (green)

- Utilisation of CO2 through carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) technologies, where the ultimate source of the CO2 (atmospheric or fossil) and the final product into which the CO2-molecules has been transformed determine the climate impact (blue)

Detailed analysis of the technological pathways, supply-chain emissions, and substitution effects is required to establish emission reduction potentials of these solutions.

Compliance and voluntary carbon markets both incentivise emission reduction or carbon removal, however each from a different angle. Compliance carbon markets aim to fulfill national or regional climate targets. By putting a price tag on emissions and they incentivise compliant actors to reduce their emissions in a cost-efficient way. The mechanics of voluntary carbon markets (VCM) aim at financially supporting projects that either reduce emissions or provide negative emissions through CDR. Private actors can purchase carbon credits from project developers to offset or neutralise their corporate emissions.

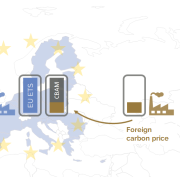

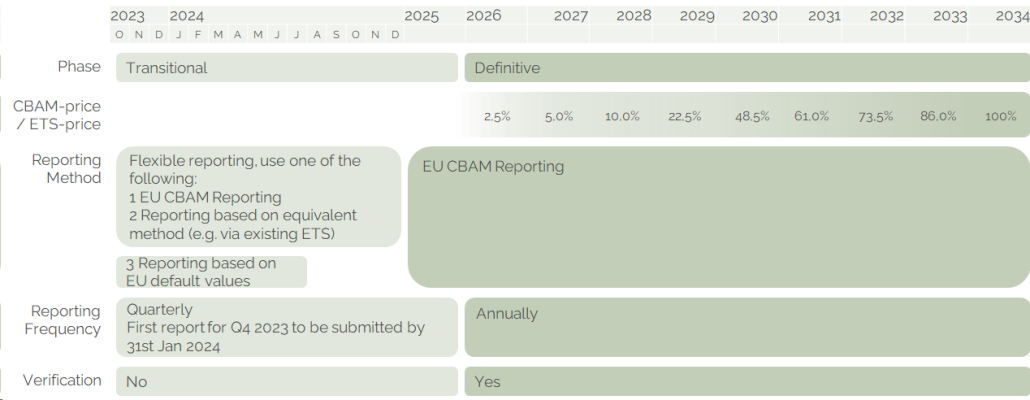

The EU ETS: zero rating for biomass

The EU ETS is one of the largest and most mature compliance carbon markets. Since its inception in 2005, the EU ETS has been a cornerstone of EU climate policy, covering 35-40% of the region’s emissions. Large industrial facilities, such as steel mills, chemical plants, cement kilns, and power plants as well as aviation and maritime transport operators need to monitor and report their annual emissions. For each ton of CO2-eq emitted, the compliant entity must surrender an emission allowance. The price of this allowance is determined at the market. Currently, many industrial facilities still receive free allowances. To prevent carbon-leakage while facing out this free allocation, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) requires importers of certain goods from non-EU countries to report the embedded carbon emissions in imports and from 2026 onwards also to pay the same carbon price as EU-based industry. Most emissions from buildings and road transport in the EU are not yet subject to a carbon price. This changes with the new EU ETS 2 covering another 35-40% of the EU’s GHG emissions. Since 2024, suppliers of liquid, gaseous or solid fuels are required to monitor and report emissions released by their fuels at the end-user. Pricing in the EU ETS 2 starts in 2027.

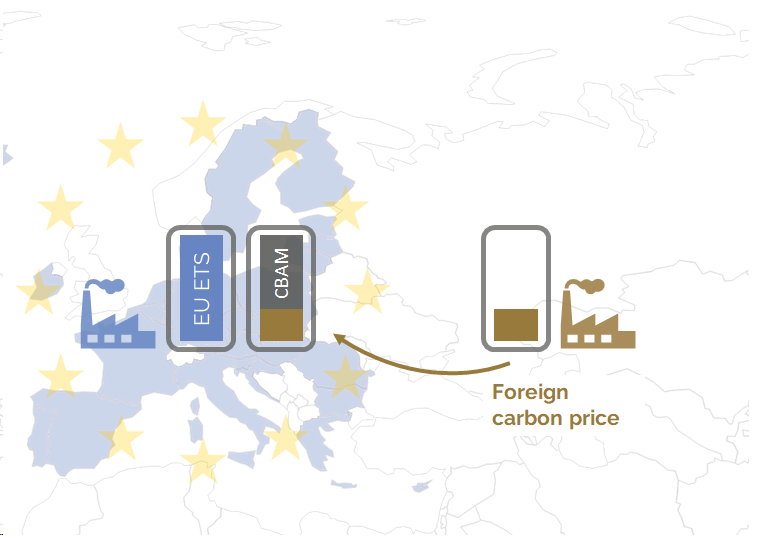

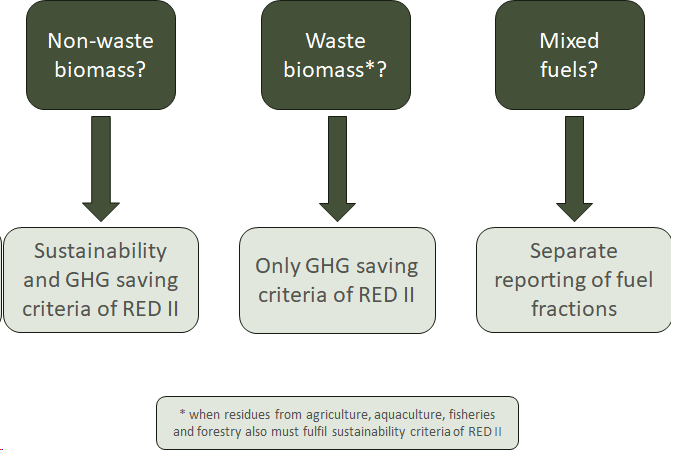

Carbon in biomass ultimately comes from the atmosphere. When combusted, only CO2 stored in the biomass is released back to the atmosphere. However, for a comprehensive life cycle assessment, factors such as land-use emissions due to biomass harvesting or emissions along the value chain need to be considered. According to current regulations, emissions from biomass and biofuels in the EU ETS 1, CBAM and EU ETS 2 can generally be counted as zero, thus reducing the number of allowances to be purchased by compliant entities and reducing their costs (Figure 2). Depending on the type of biomass and its utilisation, compliance with the Renewable Energy Directive for sustainability or GHG saving criteria needs to be achieved.

VCM: Carbon removal with biomass

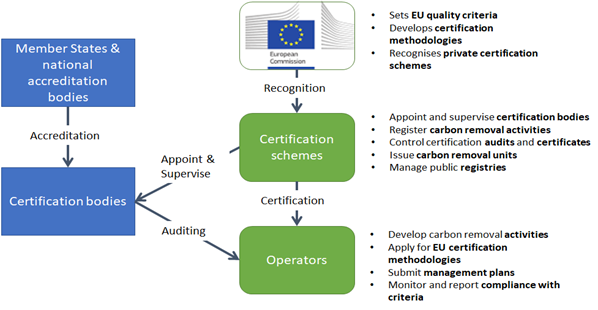

Forests, mangroves, biochar kilns and waste-to-energy plants with CCS all have in common that they are examples of biomass-based project on the VCM. Private entities purchase carbon credits from project developers to offset or neutralise their (hard-to-abate) emissions. These projects either reduce emissions or remove CO2 from the atmosphere and must follow certain standards and methodologies for project set-up and emission calculation. Third-party verification of the projects’ climate effects is needed to create trust and transparency in voluntary carbon markets where regulatory oversight is only rudimentary.

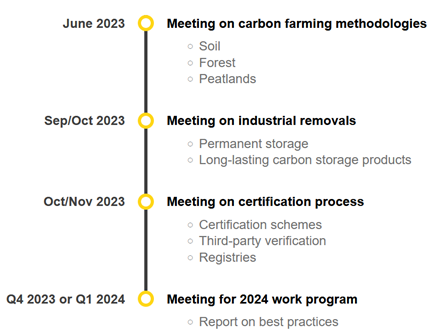

While a wide range of VCM methodologies and projects exist, biomass-based projects are ubiquitous and particularly divers. Many biomass VCM projects potentially create negative emissions (to stay within the targets of the Paris Agreement, estimates for the required global carbon removal capacity range from 5-10 Gt/year or 5-20% of today’s total emissions). While trees might store atmospheric carbon for decades, technological solutions, such as pyrolysis with biochar or bioenergy with CCS remove carbon for hundreds or thousands of years. Project developers and buyers of credits on the VCM need to navigate complexities arising from cost considerations, project types and quality, and applicable methodologies and standards (Figure 3).

To reduce the lack of credibility that has plagued the VCM and associated climate claims of credit buyers, the EU currently develops its own methodologies under the Carbon Removal Certification Framework. As corporates are increasingly under pressure to develop credible climate strategies, carbon removal solutions utilising biomass have their role to play. Several announcements of large-scale credit purchases by corporates from biochar and bioenergy with CCS project developers underscores that point.

Biomass and carbon markets: the take-aways

CO2 is not CO2: The ultimate origin of the molecule matters. Compliance and voluntary carbon markets assess emissions from different perspectives and objectives. Due to the wide array of biomass applications, rules on eligibility as well as on emission accounting in compliance and voluntary carbon market differ. Biomass use in the ETS can reduce costs for industrials and allow for decarbonisation at the same time. Biomass enables carbon removal solutions, but stakeholders need to navigate the murky waters of voluntary carbon markets. Finally, interactions between the EU ETS and the VCM might be restored against the backdrop of industrial carbon management policies, the need to scale carbon removal and to provide market stability in the ETS. Complexities abound when biomass meets carbon markets.

This article appeared first in Bioenergy International No 1-2024